Premise

Recounting the horrors of the Black Death in Florence is not the objective of this post, and it would be difficult anyway to describe the witnesses’ state of mind. That was a civilization which, although it may seem backward to modern eyes, felt at the peak of their progress after centuries of continuous growth, at the most advanced frontiers of modernity, confident in a bright future and organized within the rational plan of their religion. For the Florentines, perhaps even more so: a powerful metropolis, extraordinarily wealthy, renowned throughout the world. All this went into crisis during the years the Plague ravaged Florence, and changed the city’s future to various degrees. Hints of this can be deduced from the pages of Boccaccio, Bonaiuti, and Ranieri who were in the city at that time; from Matteo Villani who buried his brother Giovanni, whose Chronicle has accompanied us in the previous chapter; from Petrarca who never fully recovered from what he saw; from Di Cambio who buried five children in a Siena that never recovered. It is through testimonies like theirs that we will try to analyze the short-term consequences the Plague had: the rational responses of the doctors of the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali, the approaches according to social classes, the demographic and social impact; all this will allow us to better understand the economic scope of the next post.

The first attempts to stop the Plague

Starting from those who were considered the most prepared to face the disease: the members of the Art of Physicians and Pharmacists. They were a particularly large and diverse group [1], but we will limit our focus to those who were involved in the care of the sick. Those whom we will call “the medics” were independent professionals, who generally operated in the homes of patients who could afford their services, while hospitals were largely reserved for the accommodation of travelers and the infirm[2]. A medic was a specialist in human health, generally educated through years of university studies, whose knowledge was based on a refined system of classical learning, modernized by recently translated Arabic writings, along with the practice of the Scuola Salernitana[3]. Although with some variations, health was referred to as a balance of an individual’s “vital force”, where the state of illness was identified as an imbalance of the “humors” within it, according to the ancient doctrine of Hippocrates[4]. Relatively recently compared to them, the study of human anatomy had also begun to be explored in more detail, with evidence of autopsies dating back to the time of Frederick II. With the spread of the epidemic, the Pope himself would authorize and support the practice of autopsy, which was also conducted in the city of Florence.[5]. The work of the physician typically involved a visit with examination of the pulse, urine, and the prescription of specific medications [6] whose creation was handled by the Speziali (pharmacists). These could be likened to something similar to the modern herbalist: they attempted to treat afflictions of the human body with poultices or medications derived from natural ingredients[7], generally herbs, but also animal and mineral derivatives[8], in accordance with the theories prevalent at the time. Theories that, although refined, we can now understand to have been entirely useless. With the spread of the Plague, and the rapid increase in deaths, the situation turned out to be “especially humiliating for the doctors who could not offer any help, and for the most part, did not even venture to visit the patient”[9].

The organization of the medical profession did not survive the impact of the epidemic, and soon “doctors could not be found, for they died like the others; and those who were found, demanded an exorbitant price to be paid upfront before they would enter the house, and upon entering, they would take the pulse with their face turned away”[10]. For those who could not afford medical treatment, there were always hospitals, which immediately became overcrowded, unwittingly worsening the situation: the aforementioned hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, which at the time could accommodate 24-48 patients, found itself managing more than 200 per day.

The Black Death comes to Florence

The disease spared no one, indiscriminately moving through places, genders, professions, and social classes[11]. The lower strata of the population were the first and most violently affected, while the rural masses initially poured into the cities in the hope of finding care and shelter. This, we can reasonably hypothesize, led to a worsening of the general hygienic conditions previously described, such as an increase in population density in the poorer areas, and consequently an increase in mortality precisely in that part of the population[12]. The disappearance of large segments of what was effectively the workforce of the city’s industry caused long-term changes to the city’s economy, which will be briefly mentioned here and explored in depth in the following chapter. The lower clergy, who in various forms provided assistance and comfort to the sick, also suffered severe losses: in the convent of Santa Maria Novella, more than 80 religious members died[13], in the hermitage of Camaldoli, losses reached 75%. It is hypothesized that the upper classes suffered fewer losses, either due to better general health or because in some cases they fled the city, isolating themselves in country estates[14]. For one reason or another, however, the city government found itself in serious difficulty, lacking the legal quorum in the assemblies that should have guided the city in such a crisis. It thus became increasingly difficult to make any kind of decision aimed at reducing mortality, and decisions aimed at preventing the spread of panic do not seem to have been of particular significance[15]. The fact remains, however, that the city suffered an incalculable number of losses: literally, as there was not yet the idea of a precise population count, and given the mortality rate, even the tally of victims lost all sense. Boccaccio, perhaps exaggerating the horror experienced, estimated the total deaths at 100,000 for the Florence area alone; the fact is, however, that as the spaces near the churches filled up, new pits were dug where the corpses were arranged in layers to not saturate the pits too quickly[16].

Florence collapses

A population desperate to see that even the best doctors could do nothing against the Plague, soon turned to anyone who offered a hope of salvation. There are accounts of healers, mystics, sellers of miraculous remedies, so much so that “there was now a multitude both of men and of women who practised without having received the slightest tincture of medical science”[17]. Individuals who often “previously practiced the craft of blacksmithing and other mechanical arts, began to medicate and practice the art of medicine”[18].

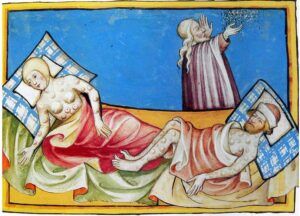

Antiquitates Flandriae (Tractatus quartus) f. 12v

Gilles li Muisis, miniature by Piérart dou Tielt

ms. 13076-13077, 1349 – 1352

KBR – Bibliothèque royale de Belgique

As evidenced by sources, such vast and sudden mortality, along with the ineffectiveness of available remedies, led to a crisis in the system of values hitherto shared by the Florentine community. The social and family fabric crumbled, and there are numerous accounts of the sick, including family members, being left to fend for themselves, as well as others locked in their homes waiting for the end, or even added to mass graves while still alive[19]. For many, the sense of striving for a future they likely would not see was lost, and they freely indulged in carnal pleasures [20] or gluttony[21]; others still “gathered in groups to eat to take some comfort […] and when dinner was made for ten, there would be two or three less found there”[22]. Others turned to displays of religious fervor, with processions of sacred images[23], while still others focused on the profit-making opportunities that, although morally questionable, arose during that period of crisis.

[1] The group included medical scholars and herb experts, but also candlemakers, stationers, haberdashers, barbers, glassmakers, and painters. Refer to Ciasca, R., Dante e l’Arte dei Medici e Speziali, in “Archivio Storico Italiano”, 89, Serie 7, Vol. 15, 337, 1931, pp.59–97 available on JSTOR .

[2] For a quick example, reference is made to the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in central Florence, active since 1289. There, patients, segregated by gender, were housed on twelve beds and cared for by oblates and conversi. Their healing was entrusted not so much to medical care as to the sacred representations frescoed on the walls. For an interesting read on healing in a sacred environment, refer to Canetti L., La medicina nel Basso Medioevo: tradizioni e conflitti, in “LV Convegno storico internazionale”, Fondazione CISAM, 2019, pp. 47-75

[3] This body of knowledge was primarily derived from Aristotelian-Galenic sources, over time augmented by works translated from the Arabic medical school and the secular medicine of the Salerno School. We will not delve into an explanation of medieval medicine, for which refer to Le Goff J., Il corpo nel Medioevo, Laterza, 2007, p. 22., or to the fascinating works of Hartnell J., Medieval Bodies, Profile Books, 2018. Remember that “medicine was not an experimental science, but an empiricism […] the physician, to care for bodies, had to deeply know logic, physics, philosophy, ethics […] medicine had lost all habit of specific analysis: in fact, caregivers did not study the patient directly, nor did they scrupulously deal with symptomatology”, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 117. Translation by the author.

[4] For a quick summary please refer to Corbellini G., Ippocrate, in “Dizionario di Medicina”, Treccani, 2010. In detail: Overwien O., Hippokrates: Über die Säfte, in “De Gruyter Akademie Forschung”, Walter De Gruyter, 2014.

[5] “Lettera di Luois Heylingen (o Sanctus) de Beeringen ai suoi amici di Brugese[…]varie menzioni di dissezioni anatomiche risalgono al 1348; in tale anno esami anatomici furono fatti a Firenze […] per individuare la cause della mortalità”, letter mentioned by Deaux G. in The Black Death, Hamilton, 1969, p.100 and following, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 116.

[6] Ciasca R., L’arte dei medici e degli speziali nell’ storia e nel commercio fiorentino del secolo XII al secolo XV, Firenze, 1927, p.289 e seguenti, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 118

[7] Richici I., L’Antico Orto Medico dell’Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova, Fondazione Santa Maria Nuova, 2022.

[8] Although these remedies might seem ridiculous to modern eyes, it is worth remembering that a scientific approach to medical art would only be achieved centuries later.

[9] “umiliante soprattutto per i medici che non potevano dare alcun aiuto, per la maggior parte non si avventuravano neppure a visitare il paziente”, De Cahuliac G., quoted in Deaux G., The Black Death, p. 59, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 119. Translation by the author.

[10] “i medici non si trovavano, perocchè moriano come gli altri; è quello che si trovavano, volevano smisurato prezzo in mano innanzi che intrassero nella casa, ed entrandovi, toccavano il polso col viso volto adietro”, Stefani M., in Istoria Fiorentina, Rub. 634, cit. Translation by the author.

[11] This, at least, we can suppose: even in this case, not enough data have survived to develop sufficiently precise statistics.

[12] “e morì tra nella città, contado e distretto di Firenze, d’ogni sesso e di cagna età de’ cinque i tre, e più, compensando il minuto popolo e i mezzani e’ maggiori, perchè alquanto fu più menomato, perché cominciò prima, ed ebbe meno aiuto, e più disagi e difetti” Villani M., Cronica, cit, chapter II.

[13] Corradi A., Annali delle epidemie, p.20 e 38, nota 4, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 165.

[14] This is also the narrative experiment that allowed Boccaccio to frame his Decameron, but these are nevertheless speculations: simply, no sources have yet been found to establish a clearer picture.

[15] Falsini A. B., Firenze dopo il 1348. Le conseguenze della Peste Nera, in “Archivio Storico Italiano”, 129, 1971, p. 425-503, available on JSTOR.

[16] “Fecesi a ogni Chiesa, o alle più, fosse infino all’acqua, larghe, e cupe, secondo lo popolo era grande; e quivi chi non era molto ricco, la notte morto, quegli, a cui toccava il mettere sopra la spalla, o gittavalo in queste fosse, o pagava gran prezzo a chi lo facesse. La mattina se ne trovavano assai in quelle fosse; toglievasi della terra, e gittvasi laggiuso loro addosso; e poi veniano gli altri sopr’essi, e poi la terra addosso a suolo, a suolo, con poca terra, come minestrasse lasagne a fornire di formaggio”, Stefani M., in Istoria Fiorentina, Rub. 634, cit.

[17] “cosí di femine come d’uomini senza avere alcuna dottrina di medicina avuta mai, era il numero divenuto grandissimo “ Boccaccio G., Decameron, cit., p.10. See also Boccaccio G., Decameron, 13, translated by Rigg J. M., London, 1921 (first printed 1903).

[18] “prima solevano l’arte dei Fabbri e l’altro arti meccaniche operare, cominciarono a medicare e l’arte della medicina exercitare“, Ciasca R., L’arte dei medici e degli speziali nell’ storia e nel commercio fiorentino del secolo XII al secolo XV, cit., p.289, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 118.

[19] The exact number of inhabitants is not known with precision, given the absence of a census at the time. The most reliable estimates suggest a population between 90000 and 130000, based on the urban consumption of grain. The calculations behind these estimates are clearly explained in Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., p. 37.

[20] Villani M., Cronica, cit., chapter II

[21] Boccaccio G., Decameron, cit., p.10-11.

[22] Stefani M., in Istoria Fiorentina, Rub. 634, cit.

[23] Stefani M., in Istoria Fiorentina, Rub. 634, cit.

One Response